Blockchain Cook County — Distributed Ledgers for Land Records

Cook County Recorder of Deeds Blockchain Pilot Program — Final Report

Overview of Blockchain Pilot Program

In September of 2016, The Office of the Cook County Recorder of Deeds announced that it would participate in a Pilot Program to study how blockchain technology could be implemented into current law and practice in Illinois land records, as well as how the state could benefit from this technology.

The Report, in PDF format, along with in-page images and other resources, can be accessed here:

Below is the full text of the Report, with formatting modified for Medium.com — the footnotes have become endnotes.

Summary of Findings

The CCRD Blockchain Pilot Program produced a series of findings and results. These findings and this Report are the opinions of CCRD or the author alone, and should not be considered shared by Pilot participants.

Result: The participants designed a blockchain real estate conveyance software workflow that can be a framework for the first legal blockchain conveyance in Illinois (and possibly the US.)

Result: CCRD has successfully used components of blockchain technology (file hashing and Merkle trees) to secure government records on a site maintained by an authorized non-government reseller.

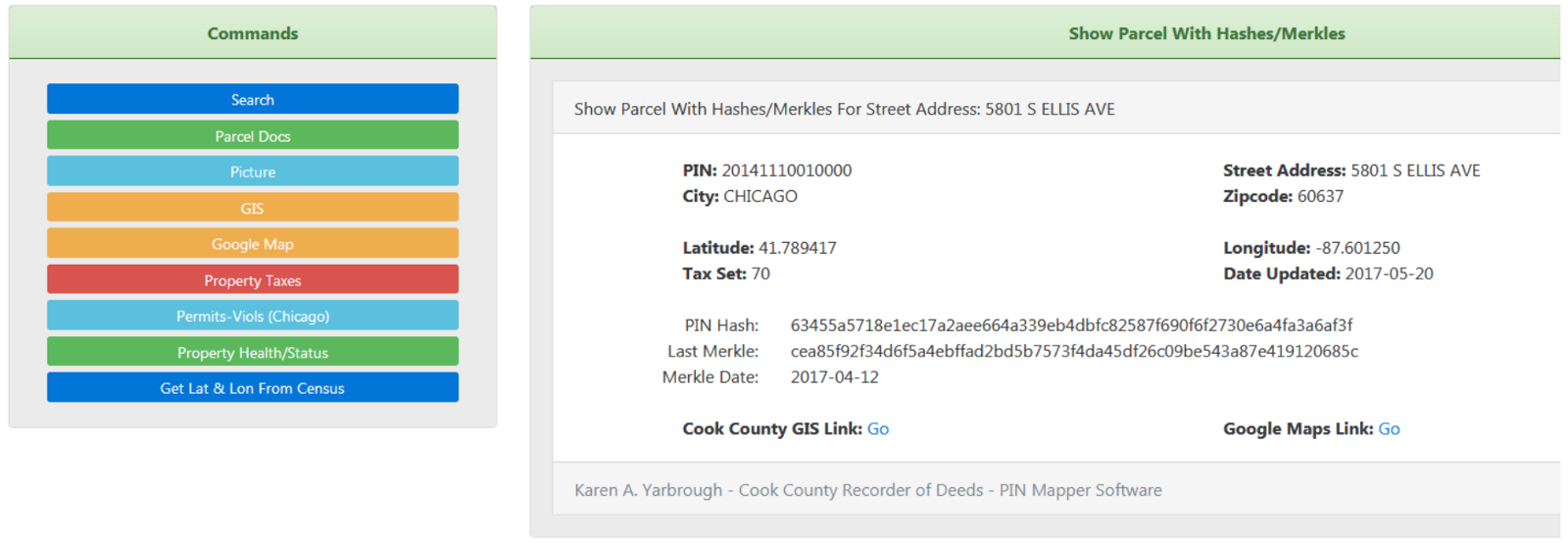

Result: CCRD used the concept of “oracles” to build the most informative property information website in Cook County, with a dedicated landing page for each parcel. These landing pages can be conceptualized as “digital property abstracts,” which help people see the benefits of consolidating important property information.

Result: CCRD’s current enterprise land records software vendor, Conduent (formerly Xerox/ACS) has agreed to incorporate some of the technology used in blockchains, particularly file hashing and data integrity certification, into the new land records system currently being installed at CCRD. Both parties will work together over the next year to explore further possible uses.

Below is a summary of CCRD’s findings and opinions. Each will be expanded further on in the Report.

- Blockchain technology is a known method for permanently storing transactional records that in a number of respects is superior to locally-isolated client-server models, and can provide a method of recordkeeping that is resistant to alteration, even by government officials.

- The use of blockchain with a Proof of Work consensus algorithm that requires expending massive amounts of electricity to confirm each transaction is not ideal for real estate recordkeeping. Distributed ledgers may be a better option.

- Blockchain can provide a mechanism to combine the act of conveyance and the act of providing notice (recordation) of the conveyance into one event.

- “Blockchain” is not an all-or-nothing approach; aspects of the component technology can be implemented individually or selectively to improve recordkeeping outcomes.

- Creating “Digital property abstracts” can consolidate property information that is currently spread across multiple government offices in one place, empowering residential and commercial property buyers, as well as lenders and other interested parties while creating a framework for a digital property token.

- Protecting property conveyances with asymmetric key cryptography (akin to locking the transfer with a secret password), would make unauthorized conveyances more difficult, protecting homeowners and lienholders.

- While digital signatures could phase out “wet” signatures from the public record and could thereby increase privacy and security, it could enable secrecy, and it remains important for Illinois’ land registry to remain open and continue to identify all who participate.

- In many cases, a parcel could be easily conveyed using the Bitcoin (or another) blockchain, but if that process also included tokenizing title to the parcel and making the digital asset a bearer-asset; this further outcome may not be desired or, if desired, may create new challenges that must be addressed.

- Separate from conveyancing, if the use of blockchain were to be extended to the maintenance of a records system, it would be most optimal if the record-keeping ledger were to be distributed across all land records offices in Illinois, allowing economies of scale and the ability to create true distributed consensus.

- With the CCRD office slated for consolidation with the Cook County Clerk by 2020, it is not prudent to undertake any large conversion effort without knowing the commitment of the elected official who will ultimately run the combined office.

A Note about Terminology

Under current usage, the term “blockchain” can refer to a well-known, specific blockchain (the Bitcoin blockchain), a custom-built private or public blockchain, or the general idea of creating an immutable, chronological ledger of transactions protected against revision by encryption and consensus algorithms. Another common industry term is “DLT,” or “distributed ledger technology,” meant to differentiate databases built upon proprietary or custom ledgers, or those built without a “Proof of Work” algorithm or an associated cryptocurrency. CCRD is well aware that only very specific use cases truly can be considered a “blockchain.”

This Report considers all forms of usage, and the author has made every effort to be clear in specific contexts to which blockchain is referenced. If a reference to a blockchain is not made clear, readers should envision a generic blockchain. The term “blockchain technology” generally means that certain attributes of a blockchain were utilized or packaged in a different way to achieve a desired result, but not necessarily in conjunction with a cryptocurrency or a widely-distributed consensus algorithm like “Proof of Work.” Perhaps the interchangeable term “cryptosystems” (coined by Ed Dunn[1]) is more accurate than “blockchain technology,” but in the interest of consistency and furthering a conversation, common usage will be employed.

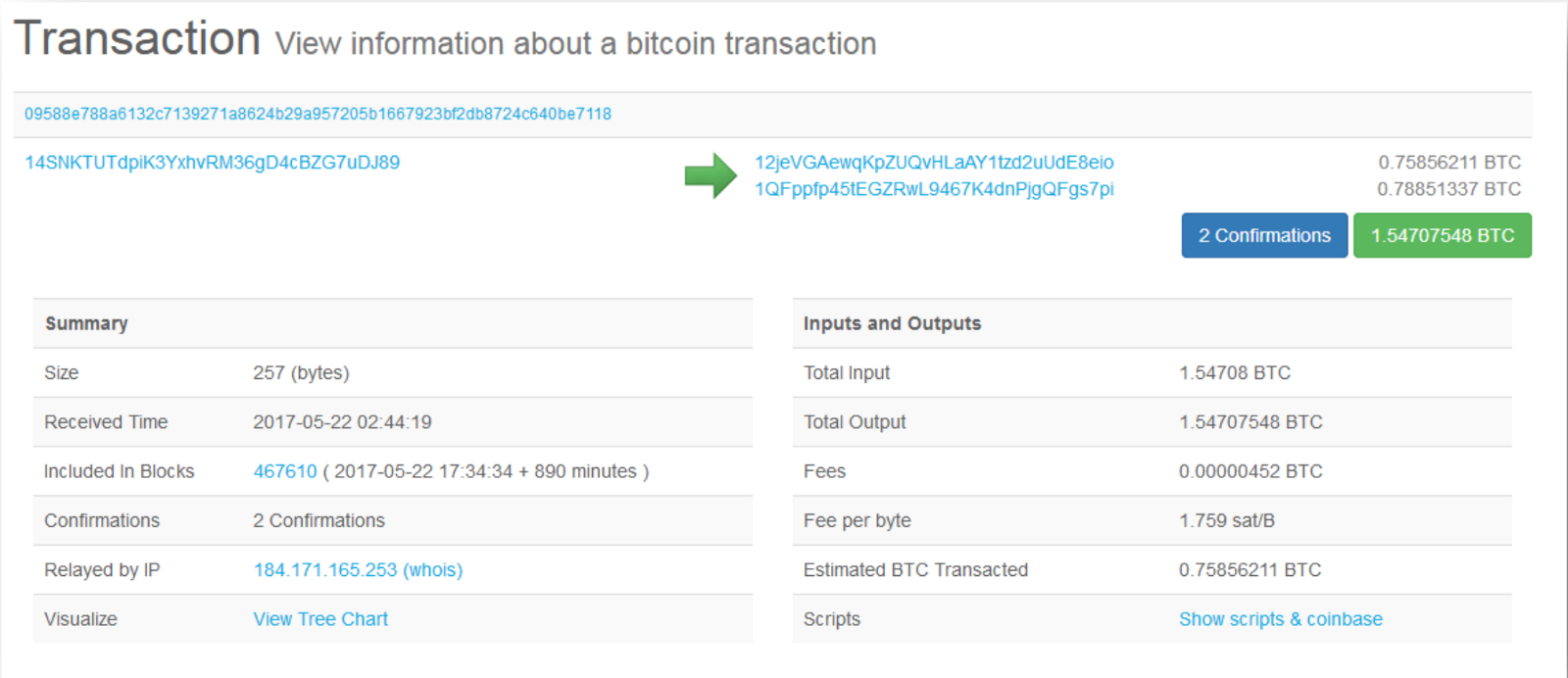

For this Pilot Program, the Bitcoin blockchain was selected by the conveyancing software company velox.RE because of its eight-year track record of immutability.

Throughout this document, the Office of the Cook County Recorder of Deeds will be referred to as CCRD.

About the Participants in the Pilot Program

Cook County Recorder of Deeds

Led by Karen A. Yarbrough since her election in 2012, CCRD is one of the largest land records offices in the United States. CCRD’s blockchain pilot efforts were led by John Mirkovic, Deputy Recorder of Communications and IT, with technical assistance provided by Don Guernsey of Onyx Electronics.

International Blockchain Real Estate Association (IBREA)

Founded in 2014, IBREA is one of the largest blockchain trade organizations in any sector (over 2,000 members), and is the leading organization applying the technology to real estate. IBREA helped develop and share knowledge, facilitated phone conferences, and served as a conduit for local informational updates and feedback. IBREA was founded by Ragnar Lifthrasir and is led by Noga Golan.

velox.RE

Orange County California-based technology startup founded by Ragnar Lifthrasir. velox.RE is a comprehensive real estate transaction and asset management platform built on Bitcoin blockchain and distributed file storage.

Hogan Lovells

Hogan Lovells, an international law firm with over 2,500 lawyers, including more than 800 partners operating out of more than 45 offices in the United States, Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, Africa, Asia and Australia. Hogan Lovells advised IBREA in connection with the Pilot Program. The Hogan Lovells team was led by New York-based partner, Lewis Cohen, who specializes in the application of blockchain and distributed ledger technology to complex financial, real estate and other transactions.

Blockchain Consulting LLC

Velox.RE was advised by Chuck Thompson, CEO and founder of Blockchain Consulting LLC. Chuck is also a member of the Board of Directors of IBREA.

Goldberg Kohn

CCRD was represented by Chicago-based pro bono counsel Goldberg Kohn, through its partners Gerald Jenkins and Gary Ruben, who assisted in legal research and reviewing this Report.

Goals of the Pilot Program

The overall goal of the Pilot Program, as stated in the press release announcing the effort, was to “test cross-compatibility between the client-server database model and distributed ledgers,[2]” but also included a wide-ranging evaluation of the legal protections afforded to purely digital transactions. This was both a technological and legal inquiry meant to discern what types of transactions can be performed today, and how records that currently must necessarily be kept in two separate databases can be linked through a means acceptable to a Recorder of Deeds.

The Pilot Program, from CCRD’s perspective, was also initiated to learn how the process of conveying and recording real estate transactions could be improved via changes to state and local laws, and what specific laws can be adjusted to encourage electronic-only legal instruments.

A second aspect of the Pilot Program, initially focusing on approximately 2,000 vacant properties in Chicago slated for demolition, was meant to demonstrate how a “digital property abstract” could be created, and show how consolidating records held by multiple government offices across multiple layers of government will result in a holistic and accurate picture of the financial health of a property. Aggregating this data into one “location” is the first step to streamlining pre-conveyance due diligence, allowing the property title to transition from a sequence of scattered events to an actual “object” (the digital abstract). The term “abstract” is reminiscent of how records about a parcel of property have been kept in the past, and like the abstracts of the past, that the digital abstract could create an ongoing story of a property.

Additional aspects of the Pilot included:

- Test and analyze the statutory definition of a real property conveyance under Illinois law and whether a real property conveyance must occur on paper

- Test the concept of unification of conveyance and notice (i.e., making the act of conveyance and the updating of the public record a single event)

- Study how a real property conveyance can be made more private while still maintaining a level of disclosure that meets the public’s needs

- Promote awareness of digital signatures

- Study the ramifications of locking property conveyances with asymmetric key pairs

- Promote awareness of blockchain and distributed ledger technology (DLT) amongst land records officials and lawmakers and ensure that government has a voice in the direction that conveyancing takes

- Demonstrate an open-minded approach that encourages Chicago, Cook County and Illinois to be leaders in this technology and to be “light-touch” regulators

It is also worth stating what this Pilot Program was not, which is necessary due to some media accounts that inferred more from the program than what was announced. This Pilot Program was not an effort to convert the current client-server database structure of CCRD to a blockchain structure. It was a study of technology and law, using a narrow data set. CCRD believes that converting its current public record, with over 190 million data points and 20 terabytes of images, would be a massive effort. With the office slated for consolidation with the Cook County Clerk by 2020, it is not prudent at this time to undertake such an effort without knowing the commitment of the elected official who will ultimately run the combined office.

These above-stated goals, unless otherwise stated, are those of CCRD.

Common Misconceptions and What a Recorder/Registrar Actually Is

Because we expect this Report to be read by many who are not real estate industry professionals, it is important to first establish a few baseline facts that should help to clear up some common misconceptions about what the public land record actually is. Additionally, the way land records are kept varies widely across the US and world, and this Section will help distinguish any practices or legal standards that may be different in Cook County and Illinois.

Because the complexity of guiding a real estate transaction from handshake to the closing table makes people reliant on intermediaries and legal experts, many homeowners are unsure or unaware of what a Recorder of Deeds office does, and what its purpose is. Further, many don’t know how they own their home (joint tenancy, tenants in common…), or even how to obtain a copy of the deed that proves their ownership. Some believe that they don’t own their home until after 30 years of mortgage payments. This reliance on third parties fosters unfamiliarity with property ownership and leads some to have incorrect assumptions about the role of CCRD and the purpose of a public registry.

A government land records office, such as a Recorder of Deeds, Registrar, or Clerk, is simply a place to provide public notice of land transactions and attendant encumbrances like liens (mortgages). The conveyance of a parcel of property from one party to another is effected by the use of a conveyancing document (typically, a type of deed), meeting the requirements of applicable law. Although they do not play a role in the actual conveyances or transactions, the public databases maintained by these elected officials serve a vital and fundamental role in the economy of the United States. Dr. Hernando De Soto, one of the world’s foremost researchers and scholars on private property rights, identified public land registries in his book The Mystery of Capital as the key to Western economic success, and stated that such a system is essential for developing nations to unlock the “dead capital” of their residents who cannot prove ownership of their own property.

The State of Illinois does not have a legal requirement that deeds and conveyancing instruments be recorded in a Recorder’s Office and, thus, recording a deed does not increase or enhance the validity of the conveyance. If properly executed, signed, accepted and witnessed, an unrecorded deed is just as “legal” (that is, enforceable by the buyer against the seller) as a recorded one. Recording a deed does, however, provide valuable protections to the new owner. Because most financing contracts and mortgages require as a condition of borrowing money that the deed conveying the property and other associated documents be immediately recorded, as do the terms and conditions of a contract for title insurance, most deeds and conveyance instruments are recorded.

In Illinois, public information about real property is hard to find. Many are surprised that no single government agency has custody over all important data regarding real property and are often frustrated that they must visit so many different offices for necessary information relating to one transaction. Most are also not aware that a parcel of real property can be fraudulently conveyed to another by simply forging and recording a new deed, something that can be done anonymously through the mail.

Another misconception is certification of records. This action does not mean that the CCRD certifies that the legal claims made in recorded documents are true, but rather, that a physical reproduction of an instrument was generated from the Recorder’s master database and reflects a true and accurate copy of what was presented at the time and date stamped on the face. Certification is normally done with a physical embosser and can be confirmed via tactile inspection.

Under Illinois law, it is possible to possess an otherwise valid deed conveying property to the grantee, but the deed not being in a format entitled to be recorded. It is a common misconception that a Recorder of Deeds must accept all documents for recording. For example, if a deed does not display on the first page the information about who prepared it, it can be rejected for recording until rectified without affecting the validity of the act of conveyance described therein. If it is not in a physical format that allows CCRD to reproduce it, the document can be rejected.

Additional clarifications:

- Though a blockchain can increase privacy and anonymity, it can also increase secrecy, and it must be recognized that the U.S. economy has long been dependent on a public land record and upon everyone being able to engage with the owners of any parcel.

- In Illinois, new deeds are always created for subsequent transfers (a deed is not a bearer-asset).

- Unlike vehicle titles with a lien, the grantee receives the property deed (and ownership) upon acceptance of the conveyance. Even if there is a mortgage, the mortgage lender does not hold the deed pending complete satisfaction of the mortgage obligation.

- In Illinois, the Recorder does not have the authority to investigate legal claims made in documents, making it easy to commit property fraud. Because the land records system is open, it is possible to steal a property (on paper) by mailing in a forged transfer instrument.

- The Recorder is not the arbiter of who owns a parcel of real property. It keeps the public record that allows others to make that determination. Additionally, unrecorded documents may determine who actually owns a parcel.

- The Recorder of Deeds’ records are the only “official” records, and at this time, CCRD only accepts paper records, or scanned images of paper documents. This means that a blockchain transfer, to be afforded notice in Cook County, must ultimately produce a paper document that evidences a transaction.

- CCRD is not legally required to record everything presented to CCRD. It is from this principle that we derive our ultimate interest in the document that is presented for recording after a blockchain transfer. Many offices around the country, however, believe they must accept everything for recording.

The Recording Process in Cook County

Before fully understanding the role CCRD played in the Pilot Program’s test of blockchain technology, it is important to understand the role CCRD plays today in most real estate transactions.

Generally speaking, the Recorder of Deeds (in most jurisdictions) has no role in a property conveyance transaction, other than selling property transfer “stamps” (and collecting transfer taxes or fees) on behalf of the County and State. It is important to remember that the conveyance and recording are two separate acts, and as stated earlier, the act of recording is not required to have a valid conveyance. This means that the Recorder of Deeds is often the last step in the process, and the owners may take possession of the property even before the act of recording. This is because the conveyance already occurred upon signing and delivering the conveyance instrument.

Illinois’ public land records system is conceptually paper-based. Although it does not specifically require that deeds and instruments be on paper, the requirement that instruments be “in writing” is so easily satisfied with paper that it becomes hard for some to envision paperless transactions. Notarization (the process of having a trusted third party confirm the identity of the person signing a document) is also hard to accomplish on anything other than paper. Further, additional technological dependencies require that some physical representation of the conveyance be provided to the Recorder of Deeds, and the most obvious and efficient way to transmit this public data is bringing the original paper-based deed or other conveyancing instrument and having the Recorder’s office make a physical copy or replica. Though CCRD has taken steps to encourage paperless submissions (increasing paperless submissions from 185,000 per year to over 350,000), the hectic nature of closing real estate transactions leaves many industry professionals unable or unwilling to try new methods.

The storage and reproduction of public records throughout history has been limited to a handful of different formats, and is even mentioned in the Bible as consisting of creating two copies of a land deed (one sealed, one open, and storing them in earthenware jars — Jeremiah 32:9). Traditionally before 1924, conveyancing instruments and liens were brought to the CCRD and left there for employees to make complete transcriptions by hand into ledger books. Upon completion, the original records were returned. CCRD then became, in 1924, the first recorder’s office in the country to use large overhead cameras to make facsimile reproductions of instruments. In the 1950s, the CCRD and many other recorder’s offices began using the more efficient method of microfilm and microfiche, a decision that at the time made sense but has proven to be a disaster as governments today struggle with the cost of converting those images to digital files because the film is deteriorating.

In the 1980s and 1990s, land records offices across the United States began transitioning to electronic database management systems (known as DBMS) that replaced ledger-book reproductions of documents with computer files created by scanning the original instruments, and replaced index books with computer databases. This era led to the adoption of electronic recording (“e-recording”), which is simply accepting documents for submission via an electronic method (e.g., a purchaser or their agent scans a paper document and then submits the image file to the recorder’s office electronically).

Though a document can arrive today at CCRD in one of three ways — over the counter (paper), mail or courier (paper), or e-recording (digital file) — the workflow for placing each of them in the public record is essentially the same. If a record is received over the counter, it is immediately scanned and converted to a digital computer file, and the original is immediately returned to the customer with a physical label placed on it indicating the time and date of receipt and its unique document number. The process is the same for documents received by mail, except that the original is returned via mail.

Before recording, each document submitted to the CCRD is reviewed for compliance with Illinois’ statutory basic recording requirements. If the document is deficient beyond the scope of a nonstandard penalty, it is rejected and must be adjusted or corrected before resubmitting. E-recordings must also meet the basic recording requirements, in addition to some technological attributes (high enough image resolution for clarity, 8.5” x 11” paper size, font size 10pt or larger, adequate margins). Electronic documents that are recorded are electronically returned to the customer with the recording timestamp electronically affixed.

All documents must then go through the next critical phase: indexing. Indexing a document is the manual extraction and keying of certain data points to enable searching and to allow the database to render a full chain-of-title by displaying each document affecting a specific Property Index Number or PIN (the unique ID assigned to each parcel). Indexing the image file to the PIN and legal description is the fundamental way of keeping the public record organized, and mistakes in this process can make it impossible to find a document that represents a valid interest in or claim against property.

Therefore, the CCRD can be seen to actually keep two sets of public records: an image file of every document presented, and various indices (e.g., grantor-grantee index, tract index). The image record is the only record that can be certified by the CCRD; the index of data, while a helpful resource meant to enable people to locate a document using a variety of search queries, is by the nature of its creation subject to human error. It is believed that most title insurance companies do not rely on the data from the indices and generally inspect each image file themselves as needed to ensure accuracy.

What are “Blockchain” and Bitcoin?

Before understanding the potential impact of blockchain, it is important to understand how the first blockchain (Bitcoin’s) works in order to fully grasp why it is so revolutionary. Bitcoin is the world’s first true native Internet currency, meaning that it can be used in the way the Internet is used (peer-to-peer), can be used like cash and without a trusted third party intermediary to validate the transaction. The blockchain itself provides the settlement of the transaction and the notarization act of timestamping, while also ensuring the Bitcoin is not counterfeit.

For many years in the 1990s and 2000s, computer scientists and cryptographers could not implement an internet-native currency because there was no technology that could perform the role of a bank, and no technology to prevent the “double-spend” (or Byzantine Generals) problem. This meant there was no way to know whether the non-physical “money” sent to someone was genuine and not previously sent to someone else. By utilizing a shared ledger, where all users hold an identical copy of the entire history of every Bitcoin transaction, a ledger that reconciles across all copies every ten minutes (average), fraudulent transactions are not accepted by the blockchain, preventing a user from “giving” a single Bitcoin to multiple people (Bitcoins exist only as ledger entries; they are not “moved” in and out of separate accounts; rather, cryptography governs the ability to transfer control of Bitcoin to an intended recipient).

The blockchain is the underlying data management structure (database ledger) that makes Bitcoin possible. The Bitcoin blockchain was a novel and revolutionary idea whose genius comes from how it was assembled, as many of its components were not new at the time (2008–9). A blockchain is based on the concept of a distributed database (where all users share identical copies of the ledger), but one that not only can be read by all, but can be written to by all. “Blocks” are containers in which to package transactions, and they are “chained” together by linking the cryptographic hashes to the prior and subsequent blocks within each block. To insert a fraudulent transaction would require rewriting not only the block containing the transaction, but also at least every block that follows it.

Bitcoin protects itself against denial of service, spam and fraudulent transactions by using a protocol called Proof of Work, which ensures validity and consensus by requiring the expenditure of actual resources to solve complex cryptographic puzzles. This consensus is implemented by Bitcoin “miners.” The miners are incented by the possibility of earning new Bitcoins, and their search for those new Bitcoins ensures the integrity of transactions on the Bitcoin blockchain. This process is the only way new bitcoin are created, and the protocol currently limits the total amount of bitcoin that can ever be created.

Mining bitcoin is a resource-intensive endeavor (electricity costs, component cooling costs), and the inventor(s) of Bitcoin utilized game theory to configure it, meaning that it is more profitable to participate in the system in the way it was designed (earning new bitcoin by helping ensure consensus) than it is to try to rewrite the transactions (it would cost more in electricity to attempt to manipulate the chain than it would to simply dedicate that computing power to mining for new bitcoin).

Though the Bitcoin blockchain is quite secure, private companies have been building their own enterprise ledgers using differing structures and consensus algorithms, or by creating an “altcoin” from the original Bitcoin code. Though there are many competing approaches as to how blockchain technology should be deployed, with partisans defending every side, CCRD has identified some key components of the Bitcoin blockchain that should serve as minimum features of any custom-built blockchain or ledger that may be used by a governmental office:

- Designed to be immutable — This concept is commonly called “append-only” or “write-ahead-only” and ensures that existing records cannot be changed, but is realized only by technological enforcement through mathematical functions designed to be one-way (output cannot be used to derive value of input).

- Distributed or shared — Full copies of each individual office’s land records are stored by each office in the network, thereby automatically creating backups in multiple locations.

- Non-repudiation — An established and publicly accepted method of digitally signing transactions is used to self-certify acts, perhaps using official PKI standards, or a means for human notaries to attest electronically.

- Designed to be autonomous — CCRD is choosing to define autonomous here to mean that when the blockchain is deployed, significant coding effort is done up front to ensure that once it begins operation it cannot fail and thus cannot require constant or even routine maintenance. It should run automatically after data is fed into it and only in the way it was designed to work.

Why Blockchain for Real Estate?

If blockchain is thought to be a solution, it is important that we describe the problems it can solve.

It is hard to deny that the process of acquiring clear title to residential or commercial real estate is complicated, requiring the participation of many people, including the buyer and seller, lawyers for each, an escrow agent, an appraiser, a lender and their counsel (generally) and a title insurer. The process of acquiring clear title is sufficiently complicated that private insurance is usually obtained to cover any potential risks. However, as Goldman Sachs found in its 2016 report Blockchain: Putting Theory into Practice, title insurance may be the only type of insurance where the cost of a policy is not based on actuarial risk (generally, miniscule, in dollar terms), but rather it is based on the actual labor and effort of title company employees.[3]

In response to the housing crisis of the late 2000s, where aspiration, greed and fraud combined to harm the global economy, the federal government began adding more regulations to an already highly-regulated industry sector. Though these reforms, specifically the combination of the Truth In Lending and Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act forms into one TILA-RESPA Integrated Disclosure (TRID) form, are meant to protect consumers by ensuring they “know before they owe,” the regulations also had the effect of making the closing process even more complicated and the outcomes more urgent and important. These reforms, in the author’s opinion, while well-intended and should end the closing-day surprises many are used to, have also made homebuyers even more dependent on “experts” such as attorneys and title searchers. This increased dependence in turn causes frustration for the general public, as they not only don’t know what is happening, but they also don’t know why or how.

Unfortunately, the increasing complexity and urgency described above will almost certainly create an environment that lends to mistakes, thus fueling a self-perpetuating system where title insurance is required to “cover” the new mistakes alongside the old ones. This increasing complexity, with many hands touching every part of a transaction, is not only the biggest challenge to implementing a new way of doing business, but it may also be the biggest reason for implementing a new way of doing business.

Why Blockchain for Government Land Records?

Property records held by governmental entities are a natural fit with a database structure that technologically binds each record to its prior record. Under current retention conventions, documents on CCRD’s land records website are displayed in reverse chronological order, with newest records on the top. Those who work in the property records industry already call the history of documents on a parcel a “chain-of-title,” making the comparison to a blockchain easy to understand. This chain-of-title is also legally immutable, meaning that records are never deleted, even if they were executed incorrectly by private parties.

These records are presumed to be unchanged by the general public who views them, and for nearly every record, that is the case. CCRD does not, as a policy, replace already-recorded document image files with new ones. In rare cases where an initial scan to capture the image by CCRD staff does not result in a clear image, the Quality Assurance process will re-scan the saved copy of the original submission, which is kept for 30 days.

Though the storage conventions show that blockchain makes sense for land records, it must solve a problem to make sense to move towards such a system. Problems currently experienced by government that could be addressed by this technology include:

Efficiency and Dwindling Resources

Government resources are scarce and mounting pension obligations are placing great pressure on the delivery of services. Blockchain can allow for improved service delivery using fewer employees, or it can enable a better service that will result in revenue for government and savings for homebuyers. It can also allow counties that lack the resources to implement electronic document recording systems to join an economy of scale. A system that is data-based rather than reliant on scanning documents and printing labels can be administered using standard desktop computers with fewer peripherals.

Accuracy

The current paper-dependent mode of executing and recording transactions requires (at CCRD) that a human employee manually inspect a scanned image of an instrument and retype the data points that are necessary for the property index to be searchable. This manual process is always at risk of error. These typing errors, combined with errors made by private parties in the preparation of the documents, create a near-accurate system and actually perpetuates the complex and costly infrastructure needed to search and “clear” titles. As noted earlier, blockchains can unify the conveyance with the public record, meaning that the public record would be an exact and perfect replica of what actually happened, adding de facto accuracy to the de jure accuracy, or presumed accuracy, we have now.

Security

Though CCRD can assert that its current database is fully backed up in multiple offsite locations and that there has been no known breach of its records, CCRD cannot say that there is a mechanism to protect against what former NSA Director James Clapper calls “the next push of the envelope,[4]” where malicious actors infiltrate systems like a Recorder of Deeds Office not to steal records, but to subtly and undetectably alter existing records, with the ultimate goal of eroding public and private-sector trust in government. Such a cyberattack, if successful, would shake the very core of our economic system and would exacerbate mistrust of government and business. A blockchain structure would make this type of attack far more difficult.

Although CCRD’s records are secure, that is not the case across the state of Illinois or across the country. Records have been lost in fires and database failures. Many offices do not have the resources to have redundant backups. Many offices do not even have electronic records and may be dependent on a physical means of storage like paper or microfilm. Blockchain may be the only database structure that is protected against manipulation by the very government stewards entrusted to maintain it. In some developing countries, blockchain is being studied and implemented for this very reason.

Stagnancy

When it comes to constructing and maintaining a public land record, the furthest that many counties (including Cook County) have advanced is the acceptance of scanned images of paper documents, including some that are a combination of type and handwriting. The first e-recording was accepted almost twenty years ago, and the document-submission industry is still trying to convert paper-only counties to this “new” technology. Blockchain-inspired technology provides an opportunity for government to self-identify the next generation of land records storage systems and participate in its adoption. For example, blockchain presents an opportunity to transition to a data-only records submission model, where only the key data points are stored as text.

Theorizing Illinois’ First Legal Blockchain Conveyance

The essence of a conveyance of property is information. To paraphrase (and reimagine) Marshal McLuhan’s famous aphorism “the medium is the message,” we must embrace the idea that in this case, the medium is not the message. The “message is the message,” meaning that the deed is not valid because it was on a piece of paper; it is valid because the information within it is clear and correct and that two people irrefutably agreed to it. Whether this message is transmitted on paper or via an electronically-signed and acknowledged event should not matter if we are to transition to paperless recordkeeping and transactions. What this also means is that we must start to think about a conveyance as simply an agreement, verifiable by a paper document or electronic file. Thus, the deed becomes what it really is — information — and not simply a piece of paper.

Through most of Illinois’ history, the only way to memorialize and convey information was paper. Though paper conveyances may be convenient, they are not the most secure, and because the conveyance and the updating of the public record are two steps under our current structure, a benefit of a blockchain conveyancing system is the ability to unify the conveyance with the updating of the public record. This future benefit may include making real estate transactions more efficient and more accurate, as the information that makes up the record is the very same information used in the conveyance.

Under today’s paper-based recording system, the information on the paper is retyped into a searchable database, which is how the public can find legal claims to a property. An error in retyping the Property Index Number means that unless another Grantor/Grantee name search is also performed, that claim may not be found and satisfied before a property is sold.

One of the main goals of this Pilot Program was to create a real-life scenario where a conveyance of real property can occur without a paper deed, while still satisfying the requirement that something that can be recorded into a county’s existing public recordkeeping structure also be produced. The ultimate purpose of recording an instrument is not to validate the conveyance or make the conveyance “more legal,” but instead is to provide notice to all, especially subsequent purchasers, that a certain person has a claim to the property. Though in the future the act of conveyance can happen within the public record, or simultaneously update the record, the existing framework in Cook County and Illinois is such that the county government record is the only official record. This does not mean that an unrecorded, but otherwise valid, deed has no standing, but it does imply that a judge may not deem that an unrecorded conveyance nailed to the town square bulletin board provided sufficient notice to invalidate the claim of a subsequent purchaser. Without placing something in CCRD’s database, a blockchain transfer is no different than one nailed to a bulletin board.

Another goal of conceptualizing the first legal blockchain conveyance was to create a scenario where a legal conveyance happened without the need to record anything. This is due to the two-part nature of conveyancing and notice. The conveyance should be able to stand on its own; otherwise it carries no more weight than a verbal agreement or a vague chain of emails agreeing to convey a property. In this regard, it is important to note that CCRD does not endorse the practice of non-public conveyances. It is our position that a public record of all transactions involving each parcel of property is the most fundamental foundation of our economy, and according to De Soto, this public registry is the most important factor of economic success in the United States. Further, government (and the people) have an interest in knowing who owns a property not only for the normal practice of holding and owning property, but more importantly to address situations where the owner is failing its community, by, for example, not maintaining the property to the point it becomes a danger to others.

Taken together, to have the protections afforded by the law, some type of paper or electronic image in “perceivable” format must be submitted to the Recorder of Deeds Office in a format that meets current statutory recording requirements. Such a submission could contain very little information, but because the public record is meant to protect consumers, CCRD insisted through this process that the document that is ultimately recorded contains enough information to satisfy a public benefit of “who, what, when, where…” including metadata that allows the blockchain transaction to be located on its registry.

To satisfy this unavoidable need for a piece of paper, it was determined that a prudent course of action would be to have the buyer file with CCRD what is called a “Confirmation Deed.” This type of instrument is not common, but it is clearly referenced by the State of Illinois as being a type of instrument exempt from transfer taxes (765 ILCS and 35 ILCS [5]). That is because a Confirmation Deed is an instrument that is designed to be recorded with respect to a prior conveyance (the blockchain conveyance, in this case) with the purpose of clearing up any potential ambiguities in the prior deed. A Confirmation Deed was identified because of the extra layer of protection that it provides to the parties, which was important in this first-of-its-kind transaction.

Summary of the Proposed Transaction Workflow

It is not difficult to create a digital token, agree that it represents a certain asset, and transfer it between two people; but if it can also be said the transfer was structured in a way as to be a legal conveyance, then it would be noteworthy.

California-based startup velox.RE, as a participant in the Pilot Program, proposed building software based on open-source technology that allows two private parties to transfer digital assets without the need for a paper instrument. Velox chose the Colored Coins protocol, which is an information layer built over the Bitcoin blockchain that allows the creation of digital tokens to represent real-world assets, and those tokens to be transmitted with digital signatures, and that transaction tied permanently to the Bitcoin blockchain. Colored Coins also allows the tokens to be divided into smaller portions to represent shares of ownership. This protocol is also used by Nasdaq in their blockchain use cases.

Velox, CCRD, and participating attorneys spent months debating a theoretical software interface that would presumably meet Illinois’ threshold of legality for a conveyance. Under Illinois law, a conveyance or deed must generally identify who the parties are (grantor and grantee), provide a description of the property, have some explicit language “warranting” and/or “conveying” the property, identify a consideration amount, and be signed and dated. For the software to function correctly, these minimum public information points must be included in the plain-text metadata of the transaction, allowing both parties to digitally sign the conveyancing language, and any member of the public to read them.

For example, the conveyancing language that is signed would need a bit more information than is traditionally used on a paper deed, but is essentially the same, reducing a multi-page deed to one paragraph:

The Grantor, Bob A. Doe of Oak Park, Illinois, for and in consideration of one hundred thousand United States dollars, conveys and warrants to Grantee, Alice Q. Public, the following described real estate: PIN 12–34–567–890–0000 with the legal description of [INSERT TEXT or HASH OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION HERE], situated in the County of Cook, in the State of Illinois. The required property transfer tax declarations have been executed and filed via Declaration ID number 123456780. Dated December 19, 2016. Signed by Bob A. Doe with State of IL digital signature fs1d8df90979089 Signed Alice Q. Public with State of IL digital signature dfd767dfd7sdfs and witnessed by Marc A. Notary, a duly authorized notary public in the State of Illinois, commissioned until 2020, who inspected the photo identification of the grantor and grantee above, and affirms their identity and confirms their understanding that they intend to convey the property described herein in Illinois, and hereby electronically affixes his/her signature fdd43dsds4trdd on December 19, 2016. The conveyance transaction instrument was prepared by Blockchain Legal, whose address is 123 Anyplace Street in Chicago, and when recorded, mail tax bill to 123 Anyplace Street, Chicago.

After the digital signing of the conveyancing language by both parties, the grantor (seller) would then transmit the Colored Coin representing the property to the grantee. Again, what would make this transaction unique is that the information or words needed to make the transaction a legal deed were digitally signed by the parties and included as plain-text in the metadata of the Colored Coins transaction.

It was also discussed that the software could encourage and incorporate the participation of a human notary. If the two parties are populating the information pertinent to the transaction on-screen in real time, the notary would be able to witness exactly what they are doing. Additionally, the information that is used to create the transaction is also populated in real-time to the Confirmation Deed, which is visible on the same computer screen. This would help the notary to understand what happened, allowing the notary to also inkstamp and sign the Confirmation Deed that prints at the end of the transaction and contains the necessary information to locate the transaction in the Bitcoin blockchain (such as block height and the transaction hash value.)

At this point, the recipient of the Colored Coin would be presumed to be the owner of the parcel being transferred, and he or she need not take any additional steps. He or she now controls the Colored Coin tied to the property and can now convey the property to another party using the same method. The word “presumed” is used because only a judge in a court of law can truly decide whether the conveyance was indeed legal, though CCRD believes that the totality of the evidence, the presence of the pertinent plain-text language within the metadata of the Colored Coin transaction, combined with the witnessing of a disinterested third party (notary), would make it difficult for the original grantor to successfully claim that they did not convey or did not intend to convey the property. The final step, recordation of the Confirmation Deed or a similar affidavit, is simply a common-sense act of insurance not meant to validate the transaction, but to protect the new owner against future claims.

Though much work was put into designing this software-based workflow, velox.RE ultimately chose not to perform a legal transaction in Cook County.

Blockchain and Cryptosystems at CCRD

Though much of the Pilot was an effort to design a conveyancing workflow and study the associated legal ramifications, CCRD looked at ways to incorporate aspects of this technology into its current operations.

Background:

CCRD has been spearheading an effort in Cook County to crack down on illegal ‘contract-for-deed’ scams where fraudsters sell homes that cannot be acquired or occupied to unwitting buyers. One of the main reasons the buyers become victims is that they were unaware that they needed to check multiple government offices to learn if the property could be acquired.

Goals of CCRD Efforts:

- Use blockchain technology in a way that provides value (not an invented use case)

- Test the creation of digital property abstracts and demonstrate the value of consolidating property data

- Secure official records on a third-party (non-government) website and enhance their reputability

One commonly-known use of the Bitcoin blockchain is as a timestamp ledger that can certify the existence of a specific computer file at a point in time. This is done by creating a SHA 256 hash (digital fingerprint) of the file, then using the bitcoin OP_RETURN function to permanently embed a hexadecimal translation of that hash into the Bitcoin blockchain by marking it as an unspent transaction. This would be useful if a Recorder of Deeds did lose their entire land records image database. If a customer had the digital file they originally submitted and also submitted it to the blockchain, they could prove that it matches this blockchain record, in essence using another public database to certify records.

Currently such a service exists — ProofOfExistence.com. CCRD did test this service and found that it (or a similar feature) could be incorporated into future land records software, but the per-transaction fee (approximately per record) made it very expensive and not worth utilizing on a scale larger than a simple verification test.

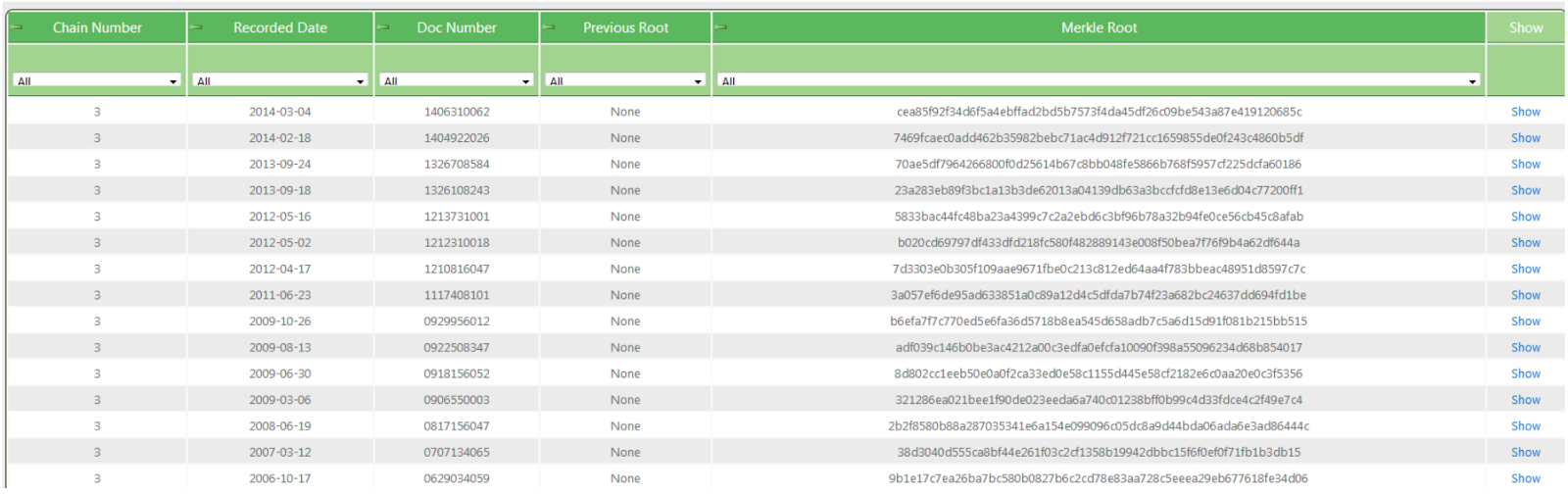

During the Pilot Program, a need to protect the integrity of CCRD records arose. The Office entered into a contractual relationship with Onyx Electronics for the purpose of reselling document images to “power users,” those who want an easier-to-use and more powerful software interface than currently provided by CCRD’s official 20/20 PerfectVision software. It became clear that blockchain-inspired technology could be used to certify the integrity of not only the files hosted on this third-party site, but also that the chain-of-title for each property could be hashed and those values used to detect any irregularities or changes in the records.

The Onyx site also, in light of CCRD’s desire to create digital property abstracts to empower those who might be deceived into buying condemned homes, became a test environment that could be customized, where the soon-to-be replaced PerfectVision software could not be modified.

The first step in creating CCRD Onyx was to copy all existing records (190 million, 20 TB) to Onyx’s servers. The TIFF images were converted to PDF, all pages watermarked for security, and the images were realigned to the indexing data, which was organized in a way to make searching faster and easier. This process took three months.

After all the records and data were transferred, Onyx began plugging in “oracles” (trusted data sources) to build the digital property abstracts for each parcel. Though it was initially mentioned that CCRD would do this for properties on the Chicago Demolition List, these abstracts were able to be created for every parcel in the County for which we could find information. In addition to each parcel’s chain-of-title (chronological history of recordings), the following information was added directly from their source:

- the photo of the property (Assessor)

- tax assessment attributes, such as lot size and square footage (Assessor)

- property tax payment and appeal history (Treasurer)

- GIS satellite map (County Clerk)

- Google Map (Google)

- Chicago building permits and violations (City of Chicago)

- latitude and longitude satellite coordinates (US Census)

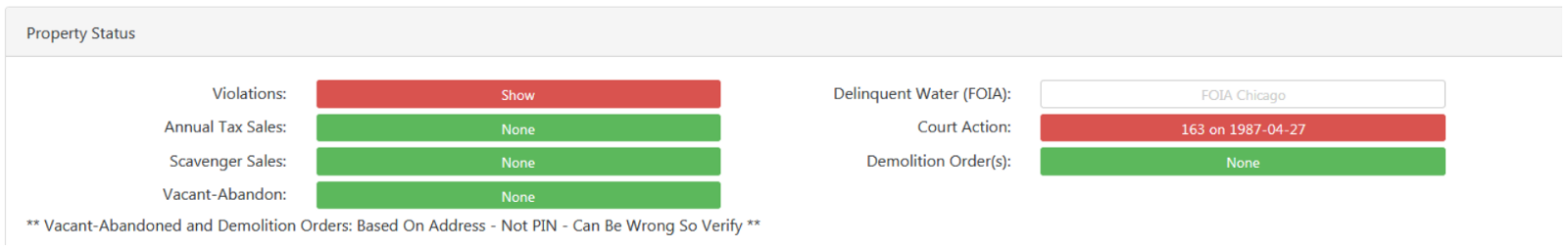

From this consolidated information, a new data visualization was created, called Property Health. Property Health allows interested investors or aspiring homeowners to see at a glance any issues that may prevent them from acquiring the property. Rather than overwhelming the user with data, the new visualization uses simple yes/no logic and color coding (red/green) to indicate whether a property may have worrisome characteristics.

For example, if a property has been sold for unpaid taxes, is or was subject to Chicago building code violations, has or had legal actions such as foreclosures, or appears on the Chicago Demolition List, the Green box would show Red, letting the individual know that the property has been flagged and more research should be done.

Once all the relevant data and oracles were implemented, the next step was to implement the SHA 256 hashing of records and construction of Merkle trees for each parcel. This process first involved the creation of three SHA 256 hash values for each document: one for the Property Index Number (PIN), one for the combined document number and recording date, and a hash of certain document image file metadata. The three hashes are then hashed together into a digest for each record. The process is repeated for each document in the chain-of-title, and the digests for each document are then hashed together to create a final Merkle root for each parcel. What results is a flagging mechanism that will alert CCRD and any public viewer if some record has been manipulated, and this flag would be triggered if any of the four genesis points has been changed. This single Merkle root value could be certified in the Bitcoin blockchain as well.

A Merkle tree is a mathematical construction used in Bitcoin and elsewhere to certify the validity of each transaction within a block of transactions and to ensure that none of the individual transactions within the block has been manipulated. The Merkle root creation also allows large volumes of data to be validated without having to examine each transaction. By imagining each recorded document as a transaction or block, each property’s transaction history can be conceptualized as an individual “blockchain.”

The Onyx software then provides a certification date for the Merkle root of each property, which provides researchers with a date and time certain upon which subsequent requests for the same data can be compared. If, for example, a hacker inserted a fake mortgage or deleted a document from that property’s chain-of-title, the hashing operation would recognize that the Merkle tree has been compromised and let the viewer know this fact. If a new document with even one pixel changed is substituted, the Merkle tree would break. As each new document is recorded on the property, the Merkle root is updated and certified with a new date.

CCRD and Onyx recognize that this usage of blockchain technology is a “cryptosystem” and not a blockchain. However, the creation of digital property abstracts and the public-facing certification of file integrity using SHA 256 shows a path forward for the next generation of land records management technology and how adopting this technology need not be an all-or-nothing approach. In fact, CCRD’s current enterprise land records software vendor has agreed that this technology should be a standard feature on their new AgileFlow Records Manager.

To be taken directly to a parcel’s hash-verification page, visit: http://ccrecorder.org/parcels/show/parcel_bc/1000000/

Expansion on Summarized Findings

1. Blockchain technology is a known method for permanently storing transactional records that in a number of respects can be superior to locally-isolated client-server models and can provide a method of recordkeeping that is resistant to alteration, even by government officials.

Prior to commencing the Pilot Program, CCRD extensively studied the blockchain technology behind Bitcoin and determined that it was successfully open-sourced, tested, and had been safely operational for eight years. Given that the current market cap of Bitcoin approaches billion, there exists sufficient motivation to find and exploit any weaknesses in its construction. Unlike other competing blockchains like Ethereum, the Bitcoin blockchain has not been exploited. Any known or reported “hacks” of Bitcoin, like Mt. Gox in 2014, were actually hacks of third party software “wallets” meant to store the private keys that must be kept secret and not a hack of the Bitcoin blockchain itself.

Contrary to popular belief, most hacks or breaches of records don’t involve weaknesses in technology, but weaknesses in people. Social engineering, for example, is much more effective in gaining access to protected systems than brute-force attacks. Because blockchain records are resistant to manipulation, even by the government officials charged with maintaining them, the technology is becoming popular as a method of reform and data integrity in the developing world.

Under U.S. law, the public record of property transactions is afforded de jure immutability, meaning it is presumed to be immutable without actually being immutable. Blockchain would make the public record more difficult to change and could, therefore, introduce de facto immutability. Implementing a truly irreversible record is not only a major step forward for technology and security, it sends a strong message that the government is interested in true reform.

Blockchain’s immutability can make it superior to a central client-server. In a true blockchain storage system, every record that would need to be stored by any office would be stored by every office. For example, every Clerk/Recorder office in Illinois could be a node in a blockchain or distributed ledger network and digitally sign off on the veracity of other office’s records. Such a distributed system would make loss of records virtually impossible, which in that respect makes distributed ledgers superior to using a centralized server. Once records are permanently secured, implementing records retention policies becomes an easy effort.

With recent news about the potential of Bitcoin becoming two separate blockchains, caution should be exercised when considering that a single registry built upon Bitcoin could exist in two blockchains, creating confusion about which is the true record. Further, having two almost identical blockchains could pose risk of a “replay attack,” where transactions sent on one chain are intercepted and reused to make identical transactions on the other.

It must also be noted that Bitcoin’s blockchain is not actually immutable as a system. As Dr. Gideon Greenspan pointed out in a recent article[6], a nation-state with a goal to destroy Bitcoin could do so for less than a billion dollars. They could accomplish this by writing their own version of the Bitcoin blockchain that meets the longest chain test (and most Proof of Work). Miners may then unwittingly begin to create new blocks on the fake blockchain. Once the attack was revealed, the value of Bitcoin would likely plunge to zero, and any records pegged to Bitcoin transactions using models like Colored Coins would likely be rendered dubious at best.

In a sense, if Bitcoin survives, it will be because of the people dedicated to updating and maintaining the Bitcoin codebase, not the codebase itself. As seen recently with the threat of a forced hard fork of the ledger into two, some leading developers are recommending changing Bitcoin’s Proof of Work algorithm to prevent this, and thus potentially removing the hashpower now held by centralized mining farms using free or subsidized electricity to gain a computing power advantage.

2. The use of blockchain with a Proof of Work consensus algorithm that requires expending massive amounts of electricity to confirm each transaction is not ideal for real estate recordkeeping. Distributed ledgers may be a better option.

Bitcoin’s blockchain is secure and immutable because of its unique Proof of Work algorithm. This type of security is necessary for a completely decentralized, anonymous and peer-to-peer transaction system. This type of consensus generation is also useful for creating general decentralized systems.

Real estate, however, is not in need of the type of decentralization required for Bitcoin. Just because one could build an anonymous peer-to-peer system for exchanging tokens they have agreed to represent real property, does not mean that one should. Most Americans depend on an open and public land records system that is kept by a single authority. This is how they can borrow money to purchase a home and tap their equity to send their children to college. A future where people are instantly and anonymously trading real estate may make sense to technologists, but its impact on our economy must be studied before heading in that direction.

What can be decentralized in real estate is the ability to submit a public record. In this regard, blockchain and DLT, if implemented alongside consolidated records and data-only records submission, can be seen as a path towards a real estate system that regular people can understand and use, one where they are not reliant on paying thousands of dollars to those who can interpret the confusing nature of how property records are kept.

The Colored Coins (tokenization) approach seems to be a secure method for transmitting information, but it is complicated and requires users to become highly educated on how the technology works, including extremely secure and encrypted means for storing the private keys. Though securing a real estate transaction behind a password or private key would be a great way to prevent unauthorized transfers of property, it is not a stretch to imagine that such a system, if it required token reuse, would result in more people losing their private keys and requiring (another) third party to sell them back their key or perform a recovery action in a multi-signature transaction (e.g. 2 of 3 keys needed to sign).

Mining Bitcoin can be conceptualized as turning electricity into currency. Conservative estimates of the amount of electricity needed to mine one Bitcoin at “5,500 kilowatt-hours — half the annual consumption of an average U.S. household.”[6] Twelve and a half Bitcoin are created through mining roughly every ten minutes. There are arguments to be made that a wholesale switch by large industry sectors such as banking to a Proof of Work validation structure would save enough money in other costs to make the increased energy consumption a wash, but the environmental impact must be understood and considered, especially for recordkeeping that is not an intensive bricks-and-mortar resource commitment.

Though the Bitcoin blockchain is the best current method for transacting value and allowing unknown parties to reach consensus, distributed ledgers may be more efficient for keeping public records that are not created in a peer-to-peer manner. This does not mean that in the future that permissioned and permissionless blockchains could not be linked.

3. Blockchain can provide a mechanism to combine the act of conveyance and the act of providing notice (recordation) of the conveyance into one event.

When one purchases a home, it is a two-step process to ensure that purchase is protected. Step one is ensuring that the conveyance by deed was completed correctly. The second step is placing a record of that transaction in the official government registry. In Cook County and Illinois, the second step is effectuated by manually retyping information from the scanned document into an index that makes it searchable by the public. This manual process undoubtedly subjects the public record to a level of error that would be eliminated by unifying the conveyance and the creation of the public record.

If the process were consolidated, the only errors that would be present in the public record would be errors created by the public before the conveyance. This is how the public land record is supposed to work, as it should be an exact reflection of what is contained in the instrument. Further, by unifying the conveyance and the creation of the record, risk of pending claims that aren’t indexed prior to a transaction (but are still valid claims nonetheless) is mitigated, as the record populates much faster, closer to “real time.” Regardless of implementation, it makes sense to explore new ways of creating public land records, including data-only or data-first submission.

4. “Blockchain” is not an all-or-nothing approach; aspects of the component technology can be implemented individually or selectively to improve recordkeeping outcomes.

The Bitcoin blockchain itself is not a single piece of technology; it is a combination of already-existing technologies such as digital signatures, asymmetric key cryptography, distributed ledgers, and peer-to-peer communication. Additionally, though Bitcoin has been in uninterrupted usage since 2009, almost all the original code from the pseudonymous and anonymous creator(s) “Satoshi Nakamoto” has been replaced. Though Bitcoin does require all the pieces of the puzzle be in place for it to work, keeping land records does not require an “all-or-nothing” approach. While it makes sense to put all similar offices in a state or region onto a shared and distributed ledger, individual offices can implement single-office private blockchain ledgers to replace their “unchained” index database.

Additionally, much like CCRD/Onyx did in implementing a hashing technology cryptosystem, there are aspects of blockchain technology that can be implemented on limited budgets. This is especially valuable to governments that may have limited resources or that wish to test certain use cases. Though CCRD prefers to wait until full-stack solutions are better developed and participation from more Illinois counties, it is supportive of the idea of individual offices implementing aspects of cryptosystem technology, and in fact, will be doing so with its current enterprise software vendor, Conduent.

5. Creating “Digital property abstracts” can consolidate property information that is currently spread across multiple government offices in one place, empowering residential and commercial property buyers, as well as lenders and other interested parties while creating a framework for a digital property token.

One of the biggest problems with transacting real estate is that the information required for pre-sale due diligence is spread across different government agencies, as well as local and state government.

Selling a used car is a relatively straightforward transaction, whereas selling a property is, at best, a complex, legal saga. While it is estimated by Goldman Sachs that 30% of property titles are not “clean” and have deficiencies, even the transfer of property without title issues is a complicated endeavor involving many people. One thing that makes vehicles easier to convey than houses is that there is not a large amount of research that must be done before buying the car. If the buyer physically has the paper title and the seller’s name matches the seller’s ID, the transaction is a simple matter, and the buyer need not consult multiple government agencies. In buying a house, relevant information affecting one’s ability to acquire a certain property exists in at least five offices, including the Recorder of Deeds, Assessor, Treasurer, Circuit Court, City of Chicago, as well as consultation of GIS plat maps held by the Clerk.

This decentralization of information is what, in CCRD’s opinion, leads people to depend upon expensive experts to help navigate this process. This reliance on others also results in a general unfamiliarity of what is needed to buy a property, and when people are not empowered with information or understanding, they are unable to make good decisions. For example, many aren’t aware that title insurance does not protect them against fraudulent claims on their property made after they acquire it.

The problem with decentralized data has become very clear in Chicago’s ongoing problem with scammers selling blighted homes as ‘contract-for-deed’ to persons who lack the resources and credit history to qualify for a bank mortgage. While in the right scenario, buying a house in very poor shape and rehabbing it can be a great way to acquire a home or start a property investing business, it is a risky endeavor if the buyer is unaware of what he or she should be looking for and where to look. For example, CCRD has encountered victims of a fraudster who sells properties he does not even own (sometimes outright, sometimes as “contract for deed”), many of which are barred from reconveyance by a judge due to their very dangerous condition. Additionally, many of these homes have delinquent utilities and water bills which must be paid before a deed can be recorded. In some cases, the amount of past due utilities and taxes equals or exceeds the value of the property, and these victims do not have the resources to come up with another ,000. In some extreme circumstances, victims pay the fraudster ,000–20,000 in cash, spend thousands of dollars of their own money on renovations, only to find that they cannot record the deed and assume ownership.

Before starting a public education campaign on what to look out for when purchasing blighted, low-value properties, CCRD felt that it is important to first create a place where all this information should be housed. Knowing that CCRD’s official public records portal (PerfectVision system) lacked the functionality to handle such a task, including the ability to search for properties by address, it was decided that the Onyx Site would best host this information. Once CCRD/Onyx was built, SHA 256 technology was used to secure the integrity of the files on the site, meaning CCRD can now tell the public that research done on Onyx is as accurate as research done on 20/20, and the hashing technology can help set time/date baselines to monitor the integrity of a chain-of-title. CCRD believes that this public-facing hashing technology should be built into all next-generation Land Records Management Systems (LRMS).

Before the Internet and digital technology, it was hard to conceptualize a property transfer as an easy task, primarily because the required information seemed almost purposefully hidden. Digital property abstracts are an important step towards building a blockchain-based property conveyance structure, and an important step towards helping people understand how real estate actually works in the United States.

6. Protecting property conveyances with asymmetric key cryptography (akin to locking the transfer with a secret password), would make unauthorized conveyances more difficult, protecting homeowners and lienholders.

Property fraud, which can consist of fraudulent conveyances or false and frivolous liens, has been one of the fastest growing white-collar crimes since the housing crash. CCRD has encountered hundreds of people over the last four years who are victims of this crime. The fact that a home can be easily conveyed illegally with paper is one of the reasons CCRD began exploring this technology.

One simple way to demonstrate how blockchain technology can create an immediate and recognizable improvement to the way real estate is conveyed is to use the example of Wi-Fi and passwords. Most Cook County residents own smartphones. Most residents have some sort of online account that requires a password. When people learn that it may be easier for their neighbor to steal their home than it is to steal their Wi-Fi, they start to grasp the security benefits blockchain provides.

Asymmetric key cryptography is accomplished by creating key-pairs (a public key and private key) that are mathematically related, as opposed to creating a single decryption key that must be securely transmitted to the entity you wish to share information with. The public key can be thought of like an email address. It can be shared with anyone, and in fact, must be shared with the person you wish to give or receive value from. The private key is analogous to a secret password and must be kept secret and secure.

Under current law and our paper-based system, a fraudster could create a fake deed using graphic design software, find the owner’s signature on a prior public record like a mortgage, and create a new deed that appears as if the owner sold or gave their house to the fraudster. At this point, the scammer need only to mail it in to CCRD and pay the recording fee (approximately ). If the property has no liens, like a mortgage, the fraudster could then use their “paper ownership” to strip the equity, rent the home to others, or sell it. If property conveyances were allowed only upon the entry of a public and private key, the unauthorized transfer of a property would be almost impossible. Even if the fraudster were able to hack or coerce the private key from the owner, the very fact that the transfer must happen on a computer makes it harder to cover one’s tracks than is possible using U.S. mail.

In addition to protecting homeowners from unauthorized conveyances, lenders would also be protected from fraudulent releases of mortgage, much like a bank prevents the unauthorized sale of a vehicle it loaned money against by physically holding the title. Blockchain, through the use of multi-signature technology, allows the creation of automated legal agreements (smart contracts) that can automate back-office tasks like the verification and filing of a satisfaction of mortgage.

7. While digital signatures could phase out all “wet” signatures from the public record and could thereby increase privacy and security, it could also enable secrecy, and it remains important for Illinois’ land registry to be open and identify all who participate.

CCRD believes that digital signature technology, a key component of blockchain, has existed long enough to have proven itself as a viable means to eliminate the need to hand-sign most documents. Therefore, a goal of this Pilot Program was to raise awareness of digital signatures and show how they can be more secure than wet signatures and how they can provide a more durable and immutable record of who signed what and when. Because scammers can use a signature found on CCRD’s website to commit further fraud with banks, landlords, etc., digital signatures can and perhaps should be more widely used.

Though these signatures can increase privacy, a fundamental aspect of the public land registry must be the clear identification of who is participating, noting that Illinois does still have a land trust system that can provide a layer of identity protection while still maintaining regulations that allow the owners to be identified when a legal need arises. As stated earlier, the service of identity verification is now performed by a notary, and will likely remain an important defense against repudiation. Some in the blockchain land records space see the technology as a way to transition to a system of anonymous property transfers, but CCRD believes such an approach undermines what De Soto identified as one of our strongest economic assets, our public land record. One idea that deserves further study is how blockchain can allow a layered approach to privacy, keeping personal information away from potential scammers while still allowing that information to be accessible either by those in law enforcement who need it, or if the owner of the data approves it.

8. In many cases, a parcel could be easily conveyed using the Bitcoin (or another) blockchain, but if that process also included tokenizing title to the parcel and making the digital token a bearer-asset, this further outcome may not be desired or, if desired, may create new challenges that must be addressed.

The Bitcoin blockchain was designed to be very good at keeping track of a limited amount of data. But, as the widely-respected Nick Szabo said, “…the limits of Bitcoin’s language and its tiny memory mean it can’t be used for most other fiduciary applications.” [8] Upgrades like the OP_RETURN unspent transaction feature in 2014 did allow small amounts of data to be encoded into the blockchain, but not in plain text. A public land registry, on the other hand, requires a larger amount of information to be stored, and to be stored in a “perceivable” format.

The Colored Coins protocol is used to add more functionality to the blockchain by creating a token to represent an asset, which is under the control of private keys, the same as Bitcoin. This process, however, can make an electronic deed a bearer-asset (property that is deemed owned by the person possessing it, not because it is licensed in a registry), like cash. If the owner of the property loses the private key or it is stolen from his or her computer by a hacker, the property token could be conveyed to an anonymous public address. Such a possibility requires the development of special protocols to safeguard keys, including the usage of multi-signature transactions or escrow services to hold keys. Additionally, some legal process would need to be created to apply for a “lost key,” similar to the lost title process for a car. Though the idea of preventing the conveyance of a property with a password may be better than the current system where anyone can file a forged piece of paper, CCRD believes that more people may lose their private keys than currently have their homes illegally conveyed, especially because Bitcoin private keys are very long and complicated (such as 5Kb8kLf9zgWQnogidDA76MzPL6TsZZY36hWXMssSzNydYXYB9KF) and cannot be chosen or memorized by the user. This issue needs further study.

Under Illinois’ current property and recording system, a deed is not a bearer-asset. When a property is sold, a new deed is created, rather than adding the new owner’s name to a master title. Keeping a record of a property’s history using a token on a blockchain necessarily requires that same token be reused. Further complications exist such as dividing ownership and thus, dividing tokens, and what to do when a parcel is split into two or more new parcels. These are all concerns that could be solved, but they do show how the use of blockchain can change the very nature of property ownership and conveyance.

9. Separate from conveyancing, if the use of blockchain were to be extended to the maintenance of a records system, it would be most optimal if the record-keeping ledger were to be distributed across all land records offices in Illinois, allowing economies of scale and the ability to create true distributed consensus.